Why Is the Blues Called the 'Blues'?

Why is blues music called "the blues"? The name of this great American music probably originated with the 17th-century English expression "the blue devils," for the intense visual hallucinations that can accompany severe alcohol withdrawal. Shortened over time to "the blues," it came to mean a state of agitation or depression. "Blue" was slang for "drunk" by the 1800s. The link between "blue" and drinking is also indicated by "blue laws" that still prohibit Sunday alcohol sales in some states.

By the turn of the century, a couple's dance that involved slowly grinding the hips together called "the blues" or "the slow drag" was popular in Southern juke joints. A rural juke would be jammed on weekends with couples getting their drink on, doing the pre-coital shuffle to the accompaniment of a "bluesman" on guitar.

Today, musicians play "the blues" in the twelve-bar format introduced by William C. Handy in his 1912 sheet music "Memphis Blues.

W.C. Handy created sequences -- verse, chorus, et cetera. But the old timers didn't really play that way. John Lee Hooker, he didn't play by bars, he didn't count -- he just made a change whenever he felt like it. He didn't necessarily rhyme all his words, neither. Whatever he was thinking, whatever came up, that's what he was singing. I think Handy was trying his best to make the songs seem as professional as possible, yet also simple to play, so he put bars to the music where you could count. Twelve bars with a turn-back.

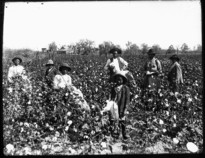

Although Handy imposed a somewhat-artificial structure on blues music, the typical three-line blues verse did emerge from call-and-response songs made up by slaves in the fields. West Africans working American fields did what they would have done at home: they improvised songs to the rhythm of the task at hand. The lead singer repeated a line twice to give another singer time to improvise a response.

I got the blues so bad, it hurts my feet to walk

I got the blues so bad, it hurts my feet to walk

This house is on my brain, it hurts my tongue to talk

-- "Lonesome House Blues", Blind Lemon Jefferson

The singing and drumming of their slaves were far more sophisticated than colonial slave-owners realized. Africans used vibrato, tremolo, falsetto, overtones, hoarse-voiced and shouting vocal techniques to convey many shades of meaning. African musicians were also more advanced in polyphonic, contrapuntal rhythms than their European peers.

Colonists didn't realize that because many African languages are tonal, drummers could mimic speech. "Talking drums" were key to organizing slave rebellions.They were banned once slave-owners caught on after several deadly uprisings. Brutal slaves codes like the Black Codes of Georgia forbade slaves from "beating the drum and blowing the trumpet" on pain of death.

These African people had suffered a profound cultural dislocation comparable to being shipped at warp speed to another planet. Many were from bustling towns along the Senegal and Gambia rivers, and were urban and sophisticated. Despite being stripped of their instruments, languages and religious practices held fast to the rhythmic, harmonic, and melodic features of the one art form that leaves no artifact -- song. In church, syncopation, polyphony, belting and call and response transformed European hymns into spirituals that rocked the walls. In the fields, these features survived in the work songs that birthed the blues.

Plantation work songs were primarily sung a cappella, but after Emancipation traveling country-blues singers used the guitar and harmonica to earn money playing picnics and dances. Over time, the blues became music that expressed the singer's struggles and passions, both carnal and spiritual. It's interesting that the instrumental solo -- relatively unimportant in West African music -- became central to the blues, which emerged in a country that idolized the individual and had steamrolled over the concept of tribe altogether.

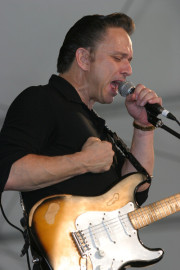

Although solos are big in the blues, they are governed by an African musical aesthetic -- the preference for emotive soul-connected playing over dazzling technical displays. Ask a blues fan who's a better guitarist -- B.B. King or Steve Vai -- and stand back.

Master African drummers collect the sticks of students who showoff, and don't give them back until the students prove they can "cool" their hearts, and play with maturity. "The blues contains those values," Texas blues guitarist Jimmie Vaughan agreed, telling me, "If a musician can get the blues and what it says about space and feeling... the space is as important as the notes. Because if you don't have space, you don't allow time for the listener to feel what has been said."

The blues invigorated American popular music with African musical techniques and values -- and rock and roll and jazz were born. Country blues evolved into the classic blues of the 1920s and 1930s, sung by stars like Bessie Smith in front of a big band or piano-led combo. The blues gave options to women like Smith and Memphis Minnie, who might have spent their lives scrubbing white peoples' floors. It made legends of plantation workers like Son House and Charlie Patton.

As Africans became African Americans, they maintained their ethics and aesthetics -- even as they were stripped of their languages and religions. What a great cultural achievement that they transferred these values to an alien world and created a new music that transcends racial and cultural boundaries, such that today blues artists can fly to Japan or Poland and be met by hordes of screaming fans who may not speak their language -- yet feel their music.

As guitarist Robben Ford likes to say, "The blues is a big house." Fine music continues to be birthed under its roof, supported by what is proving to be one of the strongest, most flexible, inspiring musical frameworks ever created.